In the Sultanate of Oman, mosques are not merely places of prayer; they are artistic masterpieces reflecting the serene spirit of Islamic ornamentation. Geometric and floral patterns, alongside Arabic calligraphy, adorn mihrabs, windows, doors and ceilings in a harmonious blend that reflects centuries of creativity.

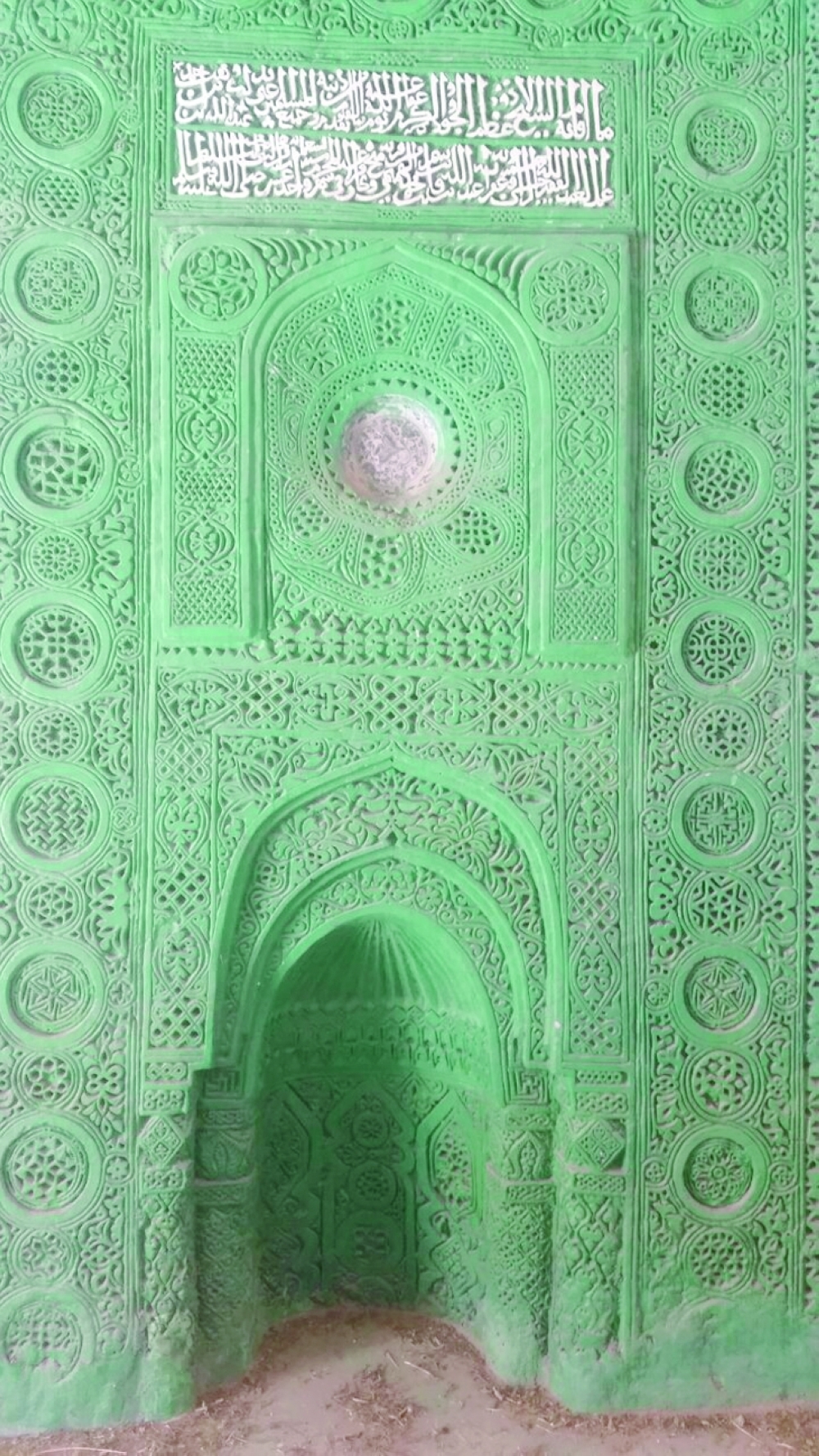

Islamic decoration in Oman’s historic mosques developed through cultural exchange with other Islamic lands. Since Islam entered Oman in the ninth year of the Hijra, Omanis engaged in conquests and maritime trade, encountering architectural styles unfamiliar in the Arabian Peninsula. As Ali bin Said al Adawi, Senior Archaeologist at the Ministry of Heritage and Tourism, explained, these encounters gradually introduced decorative richness to Omani mosques, particularly on the qibla wall where the mihrab stands as both visual and spiritual focal point. Over time, the mihrab evolved from a simple directional niche into an aesthetic composition enriched with inscriptions and refined calligraphy.

From the ancient mosques of Al Dakhiliyah Governorate — Manah, Adam, Nizwa, Bahla and Izki — and those in Al Batinah and Al Sharqiyah North Governorates, to modern mosques in Muscat Governorate, visitors embark on a visual and spiritual journey through Islamic art in its finest details.

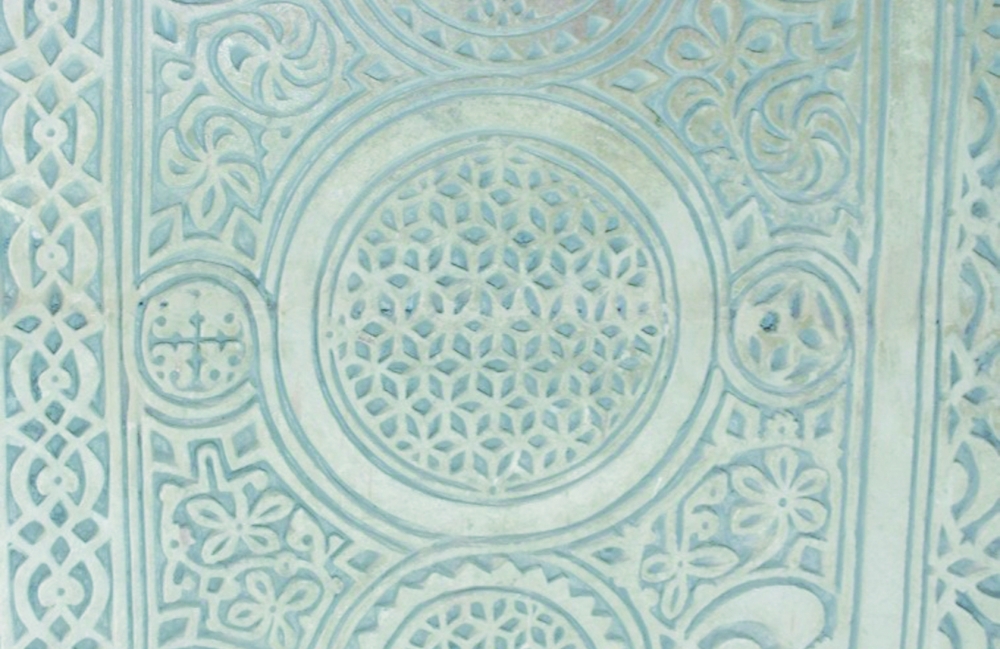

Geometric decoration forms a central feature. Simple shapes — triangles, squares, circles and stars — interlace into precise, repetitive patterns suggesting harmony and divine order. As Ali noted, the emergence of intricate structures from simple forms mirrors a universe governed by a single will. This repetition evokes infinity, inspiring contemplation and serenity.

Floral motifs, or arabesque, flow across walls, columns, pulpits and doors. Intertwining branches and leaves transform stone and wood into delicate expressions of beauty, symbolising unity of existence and divine infinity.

Calligraphic decoration speaks directly to the soul. Quran verses and inscriptions merge sanctity with artistry, connecting worshippers to their religious heritage.

Among the most remarkable examples is the historic Bahla Mosque, opposite Bahla Fort, built in the first century AH, with a tenth-century AH mihrab renowned for its scale and decoration. Its giant mihrab — the longest decorated example in old Omani mosques — bears inscriptions documenting regional history. The So’al Mosque in Nizwa houses one of the oldest surviving stucco-carved mihrabs, dating to 650 AH (1252 AD).

Research by Dr Naima Benkari of Sultan Qaboos University confirms a distinct Omani school of stucco-carved mihrabs. Emerging around the 13th century AD, flourishing in the 16th century and fading by the early 19th century, this tradition synthesised influences from Persia, Yemen, Egypt, Algeria and Iraq into a unique local expression.

A defining feature of Omani mihrabs is the prominent Kufic inscription of the Shahada crowning many 16th-century examples, surrounded by floral and geometric motifs. Another hallmark is the “outer frame” of successive tangential circles filled with carved patterns or inlaid with blue and green ceramic plates. This framing element structures the entire mihrab and is characteristic of 16th-century works.

Embedded ceramic plates — many introduced through trade with Ming China — are another distinctive element. Of the 22 mihrabs studied by Dr Naima, 20 include ceramic dishes depicting abstract florals, plants and occasionally birds or imaginary creatures. While this practice existed elsewhere, its systematic use in Oman marks a local specificity.

Carved friezes often crown the mihrab, while inscriptions record decoration dates, artisans’ names and historical context. Unlike other regions, Quran verses in Oman are frequently concentrated within the mihrab itself.

Traditional techniques relied on wooden molds, cast gypsum and direct hand carving on stucco. Craftsmen engraved designs onto molds, poured gypsum to capture floral and geometric forms, then assembled the pieces onto the mihrab. Calligraphy, including the Shahada and artisans’ signatures, was carved directly by hand. Decorative craftsmanship was historically passed through generations, though modern digital tools are increasingly used.

Dr Naima’s study shows that stucco-carved mihrabs in Oman span six centuries, with the 16th century marking their peak in quality and richness. Al Dakhiliyah Governorate — particularly Manah — was central to this artistic development.

While historic mihrabs were densely ornamented, modern mosques often favour abstract geometry and contemporary materials such as aluminium, acrylic and glass. Smart lighting and modern muqarnas further expand decorative vocabulary.

Mosques established by the Royal Court Affairs, including the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosques, exemplify this synthesis of heritage and modernity, integrating local motifs with classical Islamic design while preserving tradition.

Today, Oman continues to safeguard its decorative heritage. The Ministry of Heritage and Tourism undertakes restoration and documentation initiatives, including relocating the mihrab of Al Awaina Mosque in Wadi Bani Khalid to the National Museum. Through preservation, integration of traditional elements into contemporary design and support for artisans, Oman ensures that its Islamic decorative arts endure for future generations.

Oman Observer is now on the WhatsApp channel. Click here