Jerzy Wierzbicki’s relationship with photography began quietly, long before he

understood what art meant. At the age of three, his father placed an old Exa-1B camera in his hands and photographed him. The memory is faint, but the impact remained.

Years later, inspired by Czech master Josef Koudelka’s black-and-white documentary work, Jerzy discovered that photography was not only about images, but about truth, patience and memory.

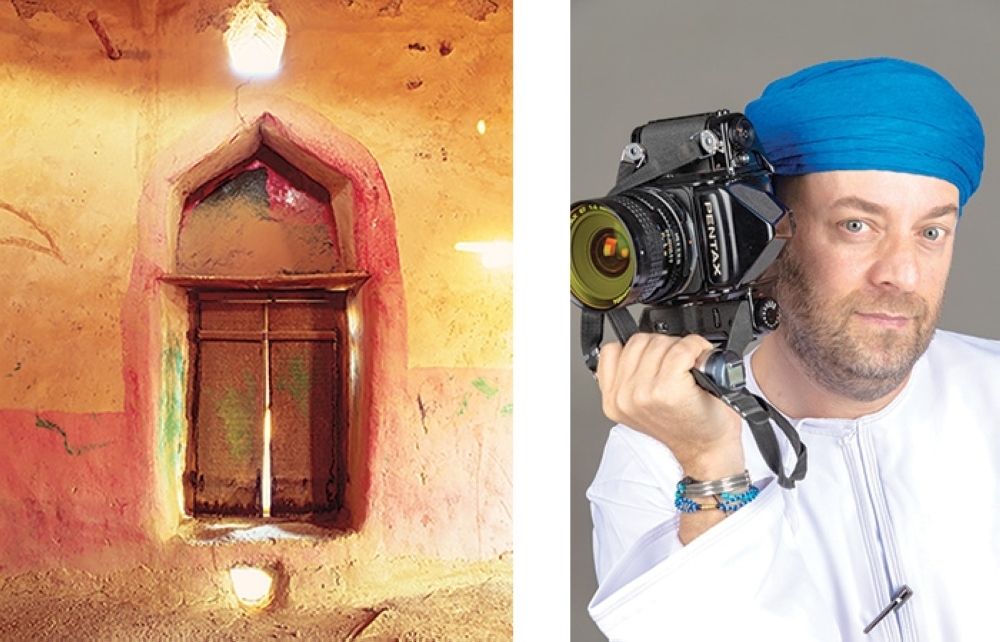

By 1993, he knew photography would be a constant in his life. Today, Jerzy is a lecturer at the Scientific College of Design in Muscat and a photographer whose artistic identity is deeply connected to Oman. “Coming to Oman seems to be the most important moment that completely changed not my photography only, but my life also”, he says.

His early adjustment to the Sultanate of Oman was not easy. The strong desert light contrasted sharply with Poland’s grey skies. Yet this challenge became a gift. The pale colours of the desert, the vast emptiness and the silence reshaped both his vision and personality.

Since 2023, he has been intensely photographing Rub Al Khali — the Empty Quarter — using only black-and-white film. For Jerzy, the desert is not just a landscape, but a state of mind.

“I prefer to create stories about the surrounding world”, he explains. “I never create artificial images based purely on technology or digital effects”. His photography is slow, physical and demanding. Each desert trip requires careful preparation, from weather analysis to film development adjusted to seasonal light. Sand once destroyed one of his cameras completely, a reminder that his work is always a negotiation with nature.

Jerzy’s photographs are held in the collections of Poland’s National Museum and

Museum of Modern Art, as well as private collections worldwide. In 2019, he presented a major exhibition in Gdansk featuring images from Dhofar and Chernobyl, two places linked by memory, loss and human presence.

Yet some of his most meaningful moments happened quietly in Oman. In Ras Madrakah, he once gave printed photographs to local people. “One young boy said that this is his first photograph he has of himself printed on paper”, Jerzy recalls. “I saw how this simple gesture would forevermore be engraved deep within his heart and soul”.

As a teacher, Jerzy believes in real experience over theory. He is encouraged that many Omani students appreciate analogue photography and handmade prints in a digital world. He sees teaching as energy: a dialogue between generations.

He also carries a deep concern. “We are overloaded with photographs”, he says.

“Making any value photography is very difficult”. Yet he believes time always rewards honesty. His own early work on Gdansk was once ignored, until it was later acquired entirely by the National Museum.

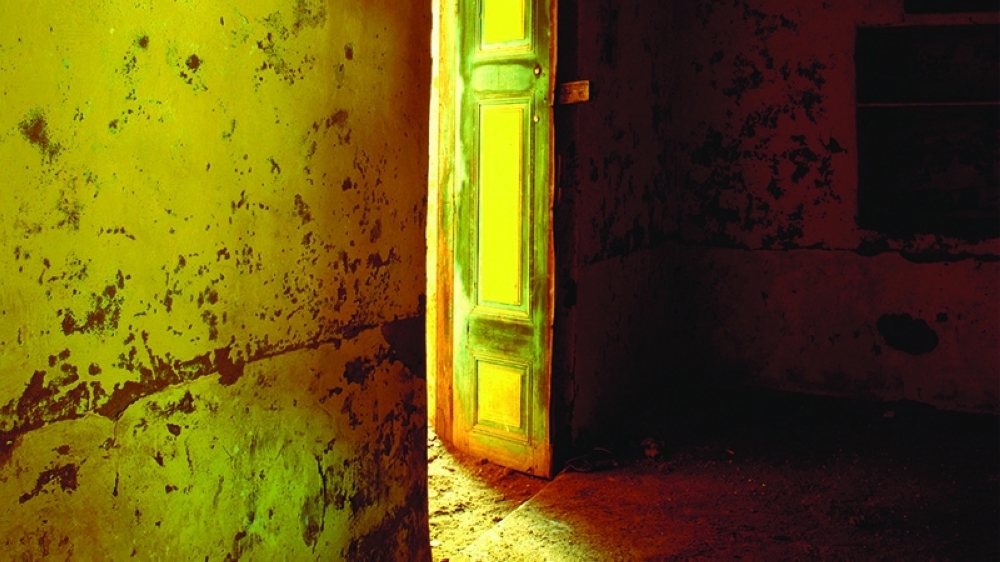

Jerzy now holds one of the largest collections documenting traditional Omani house interiors, many of which no longer exist. He still waits for the chance to exhibit them in Oman. Patience, he believes, is the artist’s greatest discipline.

His message to young photographers is simple and uncompromising: “Be honest and avoid cliché. Find a gap in the system. Be consistent and follow what you feel”.

Through deserts, abandoned homes and silent landscapes, Jerzy Wierzbicki continues to photograph not what is popular, but what will remain.

Oman Observer is now on the WhatsApp channel. Click here